Fake News: Easily Published, Impossible to Eradicate

February 15, 2017

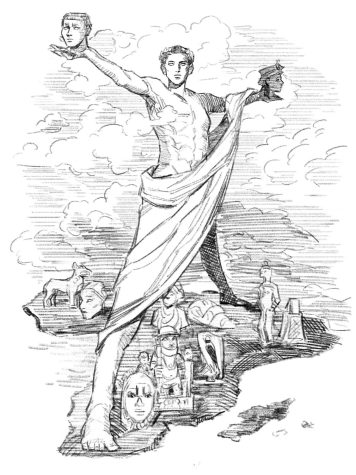

Fake news has been playing an unfortunate role in society since the Middle Ages. Politico magazine cites events similar to today’s fake news outbreaks as early as the fifteenth century, for example, when Italian preacher Bernardino da Feltre accused a Jewish community of murder, spewed a series of inflammatory sermons, and fueled brutal violence against Jews across the country.

Throughout history, fake news has flourished, from allegations about the bombing of the Maine to present-day hoaxes flung at popular politicians.

There are several logical explanations for the persistence of fake news. The first: publicizing fake news is rewarding. One thing that da Feltre and present-day mischief-making “news” sources have in common is that their lies have brought them to a higher social status than those of their fellow citizens. Da Feltre pulled together a following that the Pope could not stop, and his contemporaries collect similar rewards for whatever lies will get a rise out of the Internet. Inflammatory ersatz headlines—“Pope Francis Shocks World, Endorses Trump for President” or “FBI Agent Suspected in Hillary E-mail Leaks Found Dead in Apartment Murder-Suicide,”—generate significant attention, and therefore, profit.

Now that anybody can have his or her own news source for a pittance on the Internet, fake news is hard to control. A person with no legitimacy can make some noise on his or her website and instantly accrue thousands of dollars in advertising revenue along with various readers.

In the article, “A Fake News Masterpiece,” the New York Times documents the instant success of a man named Cameron Harris, who bought the website “Christian Times” for five dollars from an expired-domains vendor. He then published the provocative headline “Tens of thousands’ of Fraudulent Clinton votes found in Ohio warehouse,” promoted the story with multiple Facebook accounts, and subsequently made $5,000 from the sheer volume of people who viewed the page. Fortunately, as the Times reports, the county Board of Elections quickly refuted the story, and the page is now gone from the Internet.

Although anybody implicated in fake news can sue for defamation, frequent targets like Clinton and Trump are likely to choose not to sit through case after case against the writer, effectively letting fake news sources off the hook. In effect, publishers of fake news face few risks and high returns.

Money is not the only incentive that causes writers to shrug off their morals and start cranking out defamatory headlines. After all, some famous falsifiers of past ages gained more power than money. Ms. Ward, who teaches AP Economics, explains some examples of how fake news can translate directly into political power for the publisher: “Let’s take Steve Bannon, with Breitbart. He now has a position of power that he wouldn’t have had previously, and he has it because of what he wrote. Additionally, if you have a political ideology and agenda that you want to achieve—for example, if you a member of the alt-right, and you want to convince other people of your point of view—it might not be economic gain, but it might be the furthering of your ideology.”

Of course, seizing power or money by means of fake publication requires the falsifier to have a willing audience. Thus, people who consume and believe fake news are also responsible for the success of pseudo-journalism.

A recent survey by professors at NYU and Stanford focused on fake news pertaining to the 2016 election and found that about 8.3 percent of people believed fake headlines that had appeared online, and that the same proportion also believed made-up headlines that had never even appeared on the Internet or anywhere else. This study solidifies evidence that there is a significant portion of the population that will believe anything at all, so long as the idea plays well with the rest of the beliefs that these people have already ingested.

This era is unique in the sense that everybody with an electronic device is likely to receive fake news one way or another. Lillian Usadi ’17 reports that the majority of fake articles that she sees online come from Snapchat: “Snapchat has a lot of tabloid-like news. They show a lot of sketchy media sites.” Fortunately, avoiding fake news is not particularly challenging. Usadi suggests using Facebook to filter out fake headlines. “On Facebook, if you like a certain page, like the New York Times, then you see their news and it isn’t as unreliable.”

As long as there are incentives for writing and consuming fake news, falsifications will persist. These incentives are unlikely to vanish in 2017, or anytime in this century. Any insightful student of recent or ancient history has already reached the depressing conclusion: fact, truth, and reason, despite their virtue, are unnecessary and irrelevant as a means to power and success in this time.