Facebook’s Flag Filters: The Paradox of Passive Activism

December 20, 2015

On Saturday morning, November 14, many of us with Facebook accounts woke to a sea of blue, white, and red flooding our newsfeeds. Profile picture after profile picture was tinted in honor of those injured or killed the night prior; banners at the top of feeds asked if you, too, would like to show support for Paris by temporarily changing your profile picture! Perhaps for some of us, it was the first we had heard of the attacks. For others, it was a reminder of the shocking tragedy—a reminder that soon grew trite as it crowded out all other posts, including pressing articles documenting the events and their aftermath.

As the French flag crept into every Facebook user’s newsfeed, it became a show of convention rather than of compassion. Some students succumbed to peer pressure, keen to dress their profile pictures in the same colors as those of everyone else.

Owen McKenna ’17 frankly admits, “I hit the button [to change my picture] and was like, ‘Well this is useless,’ but I couldn’t figure out how to undo it, so I just left it.”

The Internet is known for its ephemeral fads, which start as unremarkable “clickbait” and transform into worldwide phenomena. Suddenly everyone is humming Rebecca Black’s “Friday”—satirically, of course—or arguing over the colors of an otherwise unremarkable lace dress. And, just as suddenly, the next trend overwhelms the attention of thousands, then millions, then billions of people. The trends are frivolous but easily dismissible; for example, Alex-from-Target’s fleeting five minutes of fame, while causing a select group of tween girls to swoon, were neither beneficial nor detrimental to the well-being of the world. When these viral movements, however, are meant to spark altruism or world awareness, the effects can oppose their original purposes.

Like distinctive school uniforms, millions of similarly colored profile pictures certainly showed solidarity and companionship within the Facebook community. As Hannah Usadi ’19 observes, “[The profile filters] have a way of uniting everyone without saying everything.”

The filters demonstrate that people are aware of and care about what happened in Paris, that all over the world there are people who mourn the loss of human life and denounce acts of terrorism. But if the goal is to unite against senseless violence and murder, why only a French flag? Paris may have rekindled the Western world’s fear of large-scale terrorism, but in war-torn countries all over the world, fear has burned constantly for years. Syrian refugees, subject to both a civil war and extremist violence, have fled to surrounding countries, Europe, and the United States, where they are met with hostility and prejudice. Death tolls in Syria numbered over 250,000 in August of this year.

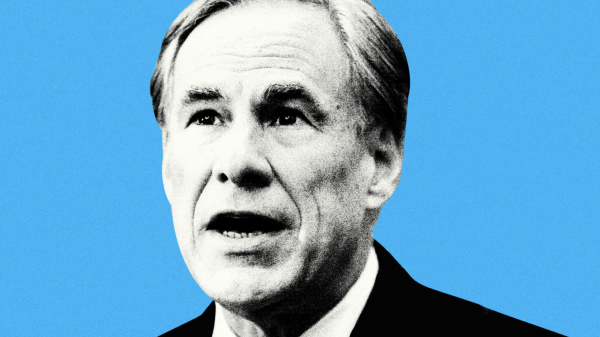

On November 17, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie’s official page posted a blue, white, and red picture of the American flag flying at half-staff in honor of the victims of the Paris attacks, writing that countries must “take decisive action… to ensure the safety of innocent people in the future.” Conversely, the day before, Christie had firmly stated in an interview that he would not be welcoming Syrian refugees into New Jersey. “I cannot allow New Jersey to participate in any program that will result in Syrian refugees – any one of whom could be connected to terrorism – being placed in our State,” Christie wrote in a letter to President Barack Obama.

The irony in his contradictions is illuminating. When participation in a movement like the flag filters is so easy and so effortless, genuine support is diluted into a weak pat on the back. The masses twist the original messages of sincere sympathy and advocacy. With a click of the mouse, guilt is replaced with self-satisfaction in one’s own altruism, leaving few to contribute to more significant humanitarian efforts. Furthermore, one can easily follow through with insignificant actions such as adding a filter to one’s picture, regardless of personal beliefs. Christie devoted himself to protecting the innocent, to combating terrorism and saving lives, yet he refuses to let even a five-year-old Syrian refugee into his state.

The intentions of Facebook’s French flag filters and their adopters were meant well, but good intentions will only go so far. When everyone has reverted his or her profile picture back to normal, the viral filters will disappear as quickly as they propagated. Blue, white, and red pictures will provoke derision (“Wow, he’s still using that filter?” or “She’s beating a dead horse now.”) more often than solidarity.

Regardless of millions of matching pictures, the world will still be replete with suffering and terrorism. No one can honestly say he or she knows how to permanently eradicate all the violence in the world, but the colors of one country’s flag draped over all of Facebook will no more end killings than the bleak colors of mourning will bring the dead back to life. The world will forget the flags, and with it, the purpose behind the movement.

sabrina • Feb 26, 2018 at 1:22 pm

i feel that the only way we could really even start to somewhat make violence disappear is to talk to each other and find middle ground.