Myanmar’s Fall from Democracy

January 3, 2020

On December 10, the International Court of Justice began its hearing, trying Myanmar on charges of genocide of the Rohingya people. De facto leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi conceded that the military may be to blame for “disproportionate force”, but denied all claims of government antagonism towards any specific ethnic group [1].

The Rohingya are a group of Sunni Muslims concentrated in the Rakhine State of Myanmar. In a predominantly Buddhist country, the two groups have clashed since the first Muslim immigration influx in Myanmar’s colonial period. While the incoming Rohingya boosted the economy, they drove down wages and outcompeted the preexisting Buddhists. With this growing anti-Rohingya antagonism, the government passed the 1982 Citizenship Act, excluding the Rohingya from the list of 135 nationally recognizedethnic groups and effectively stripping them of their citizenship. Today, the Rohingya are currently the largest stateless population in the world.

The ongoing militant violence is an extension of the 2017 attacks, when the rebel Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) claimed responsibility for a series of attacks on Myanmar police and army. The government declared them a terrorist organization and mounted a campaign that destroyed hundreds of Rohingya villages and forced out nearly 700,000 families, most of whom became part of the mass refugee crisis in Bangladesh. Fleeing civilians were shot by security forces, who also planted landmines at the Bangladeshi border.

Both the United Nations and Human Rights Watch have cited these horrors among others–mass rapes, systematic destruction by fire, and a disastrous humanitarian exodus–as evidence for ethnic cleansing. But the current case brought into the International Court of Justice is the first to formally accuse Myanmar of genocidal intent.

Gambia served as the main prosecutor for this accusation on behalf of 57 Islamic countries. Its case rests on two facets: the legislative measures taken to restrict Rohingya rights including marriage and mobility, and the ongoing decimation of entire villages of Muslims. Gambia called on witness testimonies and human-rights experts, as well as a UN fact-finding mission that found the actions of Myanmar generals to be “a veritable check-list on how to destroy a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group” [2]. The prosecution also requested that provisional measures be adopted to end the military’s campaign as the investigation occurs.

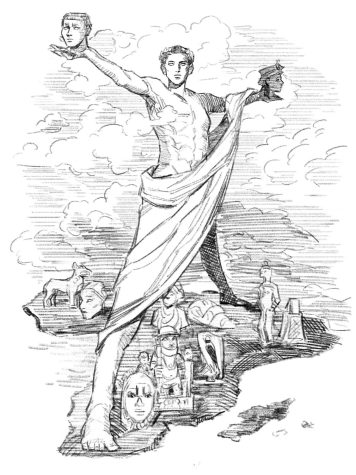

State counselor Suu Kyi, a strange figure in the midst of this controversy, defended Myanmar. Formerly a nobel prize laureate and hailed upstander for democracy, she declined to criticize the military with whom she is now locked in a power-sharing agreement. Instead, she listened impassively to Gambia’s testimony, then took the offensive against the international community. “Please bear in mind this complex situation and the challenge to sovereignty and security in our country when you are assessing the intent of those who attempted to deal with the rebellion,” she said. “Surely, under the circumstances, genocidal intent cannot be the only hypothesis” [3].

Suu Kyi insisted that her administration would hold its own investigations into potential military crimes, but blamed “impatient international actors” for involving themselves in what should have been a domestic issue [3]. She also assured the court that her government was working its best attempt to protect and uplift the impoverished Rohingya.

This first hearing was for the court to decide whether the UN should take measures to protect the Rohingya currently in Myanmar, many of which live in detainment camps. But to definitively prove the genocide allegations is a process that may take years. In the meantime, Suu Kyi, her country, and the fate of over a million Rohingya lie in a precarious position.

[1] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-50763180

[2] https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/12/10/myanmar-hearings-begin-genocide-case#

[3] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/11/world/asia/aung-san-suu-kyi-rohingya-myanmar-genocide-hague.html