Breaking Down the Zika Virus Breakout

April 20, 2016

As an increasingly mentioned household name, the Zika virus has prompted intense research in the science community. The virus captured the attention of the World Health Organization, inciting a declaration of an international public health emergency. Many average citizens are left questioning the geographic scope and mechanism of the virus. More importantly, what preventative measures will ensure one’s safety?

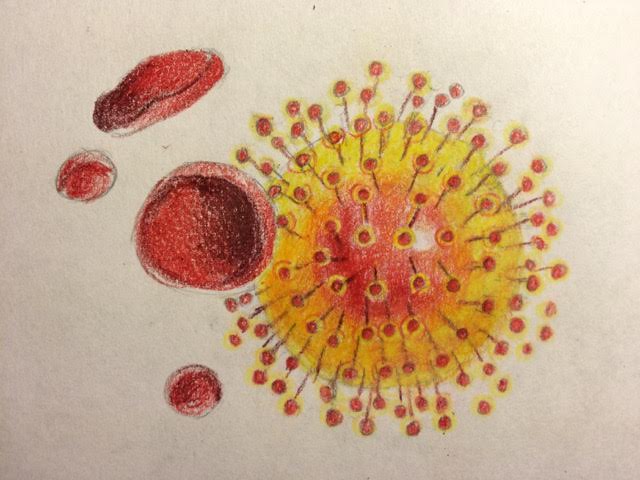

Fundamentally speaking, Zika classifies as a mosquito-borne virus, specifically linked to the bite of an Aedes mosquito. Recent cases of Zika mark a re-emergence, as opposed to a viral new development. Discovered in 1947, the Zika virus primarily traces back to Uganda, with a lingering presence in other African and South Asian countries. In the past year, reported cases of Zika have skyrocketed in the Americas.

Among those affected, symptoms vary greatly. Surprisingly, four-fifths of those who contract the virus do not show symptoms at all. The other one-fifth who are in the minority will experience a week-long fever, rashes, and muscle pain. In a majority of cases, the body heals by itself without intensive medical care. Despite its generally mild nature, the multifaceted virus may carry dreadful consequences for pregnant women.

Recent cases in Brazil may indicate a correlation between pregnant women catching the virus and newborns developing microcephaly. Since the first Brazilian case of Zika in 2015, microcephaly in babies has increased by 20 times the average rate. Microcephaly is a condition in which a baby’s head is smaller than average due to underdevelopment of the brain. Once born, the baby may experience developmental delays and other neurological complications. Despite a strong correlation, the link between Zika and microcephaly cannot be confirmed yet.

Regarding the current reach of the virus, cases extend upwards from the southern tip of Brazil through the entirety of Central America. Currently, there are no local mosquito-borne Zika virus disease cases contracted on U.S. soil, but there have been travel-related cases in about 30 states.

It is difficult to label these isolated cases as an American epidemic. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention placed a travel alert on 22 countries, advising pregnant women to avoid previously recorded areas of the virus’ presence. Due to its former position as a low priority virus, a vaccine does not exist and may take over three years to develop.

Matt Christie ‘18 strongly believes that “preventative measures to avoid the virus may include avoiding areas with dense mosquito populations. It is in our best interest to isolate these cases by abiding by the travel alerts.” He alludes to the World Health Organization’s list of safe practices, such as wearing insect repellent, covering the body with sturdy fabric, and cleaning personal belongings. As spring break approaches, many Ridge students can benefit from these small tips as they travel beyond American borders.

On the topic of prevention, Emily Wang ‘19 reflects that “informing the public proves to be the most viable option at the moment. The science community should establish a bridge between local governments.” Establishing such a bridge will allow people with different expertise to work in conjunction. The Ridge community can play an active role in informing peers of the virus and supporting current efforts to combat the virus.

Despite the virus’ complexity, the average citizen should take notice as new advancements unfold.